Full Metal Jacket: Programmed to Conform

From the first seconds of Full Metal Jacket, the individual is being shaved down to the scalp. A wide creed of hairstyles of our recruits is all being sheared as “Hello Vietnam” twangs in the background. All of these men, their histories, hopes, and desires, are all bound to be ground down to paste. The name of the paste-grinder is Sergeant Hartman.

I’ve heard a common consensus repeatedly: “whatever Kubrick film you last watched is your favorite”. This a sentiment I don’t fully agree with but I understand, considering the considerable quality of most of his career filmography. There’s a small number of his “s-tier” films where I find myself changing my favorite of his. Full Metal Jacket is certainly in that esteemed highest tier and I might consider it his best on some days— just like that consensus. For a filmmaker who intended to be simultaneously at the intersection of deliberate and opaque, it is probably his most hypnotically haunting and incendiary work.

There is another common consensus but just related to Full Metal Jacket. One that posits: “the first half, the boot camp, is excellent and the second half, the war, leaves a lot to be desired, a notion I find entirely wrong. Full Metal Jacket is a film that operates entirely on its two halves, or parts, to create its broader thesis. Part one is programming the machine. Part two is the machine in action. The thesis: war, or as the film alleges the doctrine of Uncle Sam’s armed forces during Vietnam, turns the individual into a homogenous collective, a machine, a tool for mass murder.

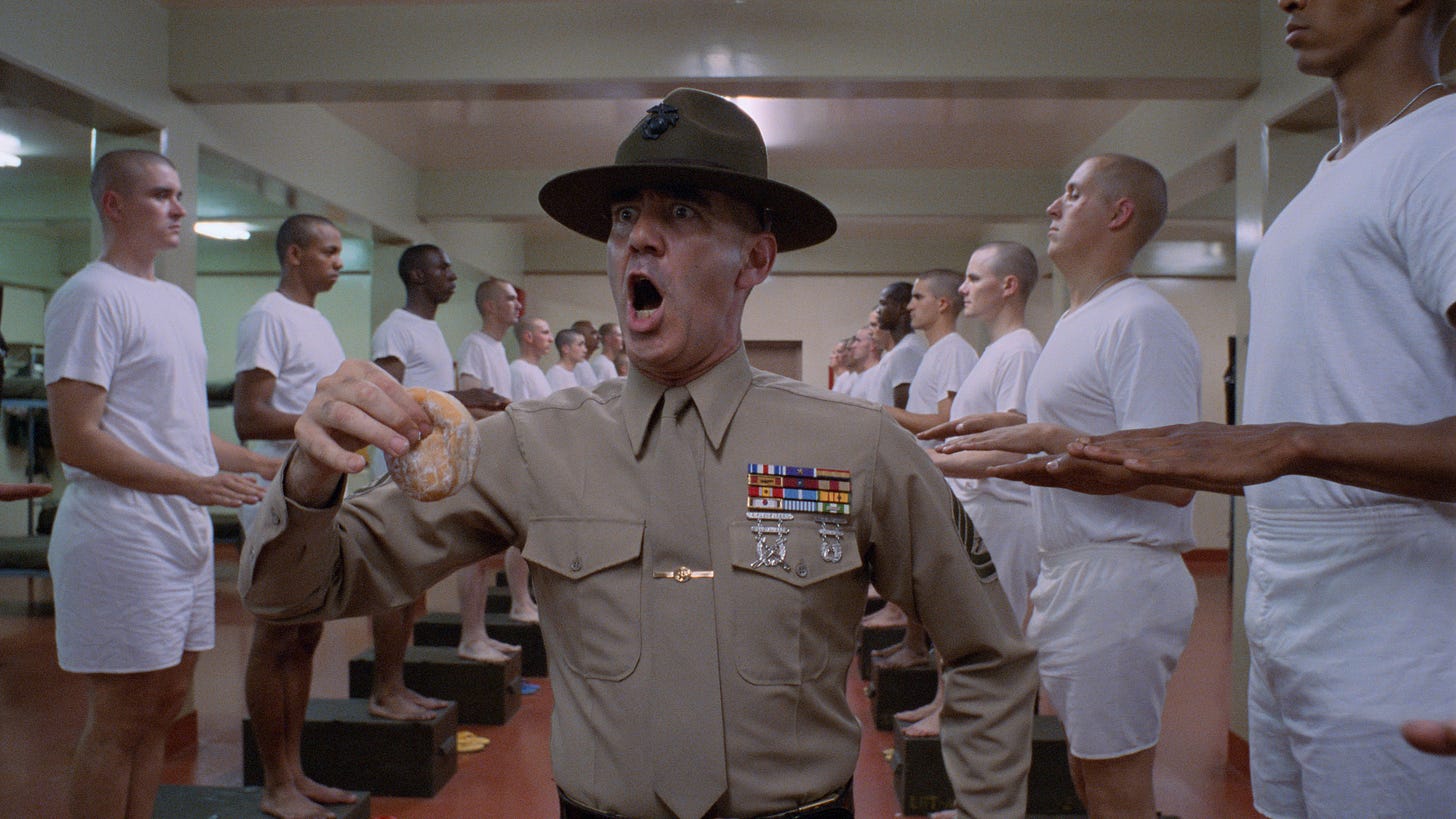

If you haven’t seen the first half of Full Metal Jacket, I’m sure you’ve seen some of its more quotable moments or enduring images on the internet. R Lee Ermey as the Marine Drill Sergeant Hartman flailing insults to recruits, a still of R Lee Ermey pointing over the camera with some boomer diatribe with impact font, or in more recent years the film has maybe the most famous “Kubrick stare” as Private Pyle (Vincent D'Onofrio) begins his break from reality. The fact that Hartman’s diatribes are considered “great movie insults” or can be co-opted for reactionary memes means these posts don’t portray his character quite the same way Kubrick intends. In the film he’s a bigot and bully, often belittling minorities or singling out Private Pyle for his overweight physique, oafish child-like qualities, and general ill-fit with the military. When I watched Jacket at a party earlier this year my friend pointed out something to me that I didn’t notice when I watched the film last as a teenager: Hartman is attempting to mold Pyle into an Animal Mother, the muscular borderline psychopathic foot soldier who totes a large machine gun who is seen in the film’s second half.

After this conversation with a friend I began to feel myself on the film’s wavelengths, it was when its eerie borderline fascistic nature began to unnerve me. The fascistic nature extends to stuff such as Ermey’s hollering drill instructor mannerisms and the songs that soldiers would chant in unison during marches. These scenes are marked with a mix of formally tense and sterile filmmaking. Either the camera entirely is still, with no movement, as Hartman berates the recruits or the camera tracks the recruits as they engage in running marches or training, uninterrupted and leaving the screen to linger on their conformity. These recruits are being reprogrammed at their core to become killing machines— but sometimes you get a killer that doesn’t program correctly. Take when Hartman mentions former Marines like Lee Harvey Oswald or Charles Whitman— who he says are great gunmen but they have their wires crossed “wrong” unlike an Animal Mother, who kills for Uncle Sam’s enemies. Pyle ends the first half chaotically, killing Hartman and himself in the barracks bathroom with his rifle. He’s a killing machine but missed the target the programmers intended for him. His wires crossed.

The second half is told through the eyes of Private Joker (Matthew Modine), presenting a battle: the war of the self vs the collective of ideological fascism, the machine in action. Joker is a walking contradiction. A cultured man with John Lennon spectacles, wearing a helmet that says born to kill and a peace pin on his uniform, he explains this Jungian significance of duality to his superiors who complain about the peace sign– but they don’t understand or care if he just does his job, US state-sponsored war journalism and the occasional kill. Presumably a draftee and not a volunteer, Joker tries to rebel against conformity through performative actions but also this presented liberal attitude and outlook that mocks the war, however, his actions are merely posturing in nature. Sure, he is markedly more informed or cultured than the other soldiers we see in the second half and probably a much more empathic person, but still submits to the conformity and authority of the military.

The other soldiers of Full Metal Jacket are a mix of the conformed to kill. In Vietnam, we see a ragtag assortment of US soldiers who have all but dehumanized the enemy. The way Vietnamese people are framed from a considerable distance (anywhere from long to extreme long shot) in its shot compositions or show the bodies of dead citizens. This represents how the American forces dehumanized the enemy, soldiers often refer to the Vietnamese people as subhuman, defaulting to calling them anti-Asian slurs. This is the type of ideology that allows people to thrive best in Vietnam. Consider a scene where the helicopter machine gunner (Tim Colceri). He is seen taking glee in mowing down civilians, nondescript in how he gets outside the Helicopter door—without care to what Vietnamese citizen is a part of the Viet Cong (or “Charlie”) or not. “War is Hell” he cackles as the scene crossfades into the next.

Full Metal Jacket’s final thirty minutes is its final descent into its heart of darkness. The beginning of this last set piece starts in the evening and descends into dusk. A Vietnamese woman is holed in a building and sniping American soldiers, culminating in Joker shooting her and then finally “mercy killing” her in cold blood rather than letting her suffer. Following this set piece, we are shown the film’s final scene; the darkest depths of the night as buildings smolder in bright red and orange flame, the only light of the scene. Joker and his Marine comrades sing the Mickey Mouse club song as they march. Joker claims “I’m in a world of shit but I’m alive!” in his narration over this image. This final scene cuts to black as the needle drop of the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It, Black” plays its opening notes and the end credits begin. It’s over but our characters have entered the darkest of the night. Is Joker finally programmed to kill? Does it matter in the first place? His brand of individualism was never rebellious in the first place.

I can’t help but think of the concept of author Philip Roth’s “indigenous American berserk” representing the second half of this film and its broader thesis on war and American intervention, the idea that there’s this subconscious antithetical violence and fury to the typical American values. I can’t help but think of this when Joker impersonates John Wayne and or when the film plays “Surfin’ Bird” to combat (a touch I presume is from Michael Herr). There’s something that lurks underneath all of these men and it’s a mean and murderous id. Yes, these GIs are programmed to kill, but they’re also born into this American berserk world of shit.